When I read the recent article The U.S. Navy’s Toxic Culture, published under a pseudonym on GCV, I wept like a child. This is not something I do lightly. Outside of my closest friends and family, few have ever seen me cry. In my industry, emotional restraint and control are considered the highest virtues. But in that moment, my composure failed me.

I have spent my career walking through or kicking in doors others would rather leave closed. I have faced the darkest corners of human suffering—suicides, overdoses, child sex trafficking, and human smuggling. I have justifiably evicted entire families, knowing the devastation it would bring. I have fought brutal legal battles, levied fines that I knew would break the backs of struggling tenants, and tried to compassionately enforce policies that left little room for sentiment. I usually feel nothing. This is what it means to be a manager. This is the weight we carry. And this is what scares many people.

I earned the nickname “The Angel of Death” because when I arrive at your door, it means your time in that home is over. “I am the one who knocks.” But even someone like me has fears. And my greatest fear? That my brother—an active-duty sailor who gave twenty years of his life to nuclear submarines before transitioning to recruitment—would become a statistic.

The cost of service is not just measured in deployments or duty rosters. There is a genetic component to depression which is seen as shameful, a physiological cost to disturbing the natural circadian rhythm, an insidious toll extracted by hot-racking—forcing three men to share a single bunk in a system so grueling we would not impose it on a police horse or K9. These are the stories we hear in passing, the realities we rationalize away. But I cannot ignore them. I will not ignore them.

The statistics do not lie. Suicide among U.S. sailors is at a four-year high despite the implementation of well-publicized initiatives, each heralded as the solution—the Clay Hunt Suicide Prevention for American Veterans Act, the BRANDON Act. Each was labeled evidence-based, yet the data tells a different story. The reality is this: meaningful change does not come from bureaucratic gestures or well-crafted soundbites. It comes from systemic, sustainable action. And yet, what does a civilian like me know?

I know that too many veterans end their lives each year.

I know because I have found them.

In my sixteen years as a property manager, I have lost count of how many I’ve discovered after they made the devastating choice to escape a world that no longer made space for them. They leave behind notes—pleas for someone, anyone, to care. Some do so in final acts of protest, desperate to force the world to acknowledge their suffering.

Sixty percent of them served in the Navy.

His name was Dante.

Every property manager who has worked in this industry long enough has a Dante. Mine was a sailor who spent years serving on aircraft carriers, working tirelessly in the galley. He was Jewish, as I am. He was Black. He was HIV-positive after his commanding officer encouraged injectable drug use to keep up with the demands of their shifts. He had lung cancer from asbestos exposure. He had lost half of his toes to diabetes and was going blind for the same reason.

Near the end of his life, Dante told me why he had trusted me. He said he saw a young, strong, yet struggling woman with a brother-shaped hole in her heart, and he could not help but step up to fill that void.

I first met him after a taxi driver became aggressive with me in my office at a Section 8/202 property in Oak Cliff. I was alone—three layers of bulletproof glass separated me from my colleagues. Dante saw how I held my ground and my hands trembling after the driver left. We made eye contact as we noticed that he had parked discreetly near staff parking, waiting. Dante—who struggled to stand for long periods—planted himself between me and the exit, unwavering. The very sky could have fallen, yet he would not abandon me. He walked me to my car that night. And with his 6’6” frame and quiet, commanding presence, no one dared challenge him.

There is no happy ending here.

There was no cure for Dante’s cancer. His family did not remember him in his final years. He was left to navigate his last days in abject poverty, mourning the brothers he lost in service, feeling abandoned by the country he once swore to protect. Every day became a struggle for survival.

But there were moments of light.

Dante loved ice cream. He would buy the nearly expired cartons from the discount grocery store, rolling through the office and common areas, eating straight from the tub. I would chase after him with a dishcloth, both of us laughing as I wiped away the drips of melted ice cream trailing in his wake.

This is what I hold onto.

Those outside my industry often do not realize the patterns. When a veteran decides to end their life, there are always signs. They clean their apartment. They take out the trash. They set the air conditioning as cold as it will go. They leave behind as little mess as possible—an unspoken apology to those who will find them. Almost all of them die clutching a memento of their service: a commendation medal, a Purple Heart, a gold star. The only exception I have seen held a lock of his mother’s hair and a handkerchief still scented with her perfume.

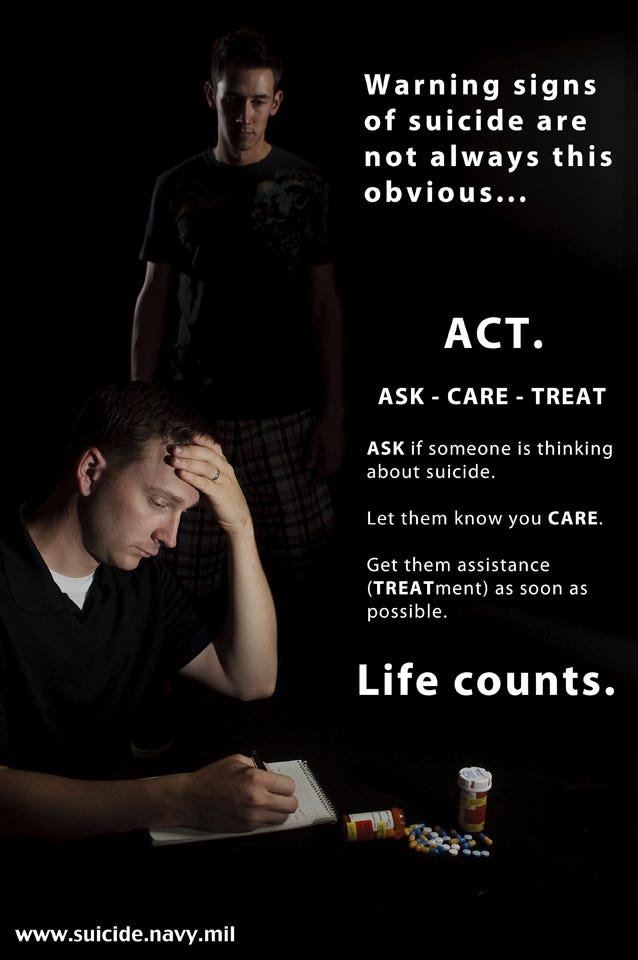

Awareness is the first step, but it is not enough.

You do not have to thank veterans for their service over and over. You do not have to have the perfect words. What they need is simple:

Listen. Believe them. Do not diminish their struggle.

Property managers are uniquely positioned to be the front line in veteran suicide prevention. We know our residents. If you do not, you should. Remember their names. Check-in when they go silent. Be mindful of death anniversaries. Recognize the small but telling signs of distress. Build relationships with the VA, housing authorities, and veteran support organizations—not just on Veterans’ Day, but every day. Make your property a true refuge, not just another battlefront.

Sit in the discomfort with them.

Let those who have been conditioned to see tears as weakness know that they are safe.

And above all—act.

The time for empty words has long passed.

Acta non verba.

Bessie

Rest in Peace, Dante.

1970-2019

Well, I just cried for the second time today. An absolutely beautiful essay.

Thank you, Shane. It is a sad honor to share this story but important to do so. And I agree that Dante gave his life in the service of this country. Thank you for seeing that about him.