(Editor’s Note: The introductory narrative is a composite of several stories which have been shared with the author, whether directly or through the media)

She turned towards the wall and pulled the sheets over her head. On the other side of the bedroom door, she heard her mother sigh and quietly walk away.

It had been 10 days since the Taliban’s barbaric assault on the girl, and yet not one moment of healing had occurred. Her thighs were bloody and discolored, and the screaming pain of her insides—which had been violated by both her attackers and their many weapons—made it impossible to walk. She bled so often that her mother had to change her sheets multiple times per day.

Many of the girl’s fingernails had been torn or ripped off. Her eyes were so swollen that she couldn’t see herself in the mirror—not that she wanted to. Her right arm and wrist hung limply by her side, fractured and useless, and her pulsing headaches left her retching on the floor.

There was not one inch of her body that had been spared from the assault, and the girl knew that she would bear the scars forever.

The Talibs had not only attacked the girl but also publicized it. They recorded the entire thing, from the moment the child was stolen from her home until the moment she was discarded on the side of a road, left to die. The sounds of the girl’s screams were often drowned out by her attackers’ laughter, which was genuine and gleeful—delighted by her pain and their own roles in inflicting it.

Following the attack, the Talibs had sent video to the girl’s friends and family members. Her father hadn’t been able to look at her since—the cursed image of a beloved daughter who could not be protected from the evils that patrolled the streets just outside their door.

Images of the assault had also been broadcast across social media. While some media outlets refused to publish the content, others declined to protect the girl. “The world must see what they are capable of,” they said.

There would be no refuge for the girl. The Talibs had weaponized her womanhood, her innocence. She had been shattered and could never be whole again.

The crime leading to her punishment? The girl was 15, and she wanted to go to school.

---

This is the reality of Afghan women and girls currently living under Taliban rule, which all but criminalizes their mere existence.

It hasn’t always been this way. Afghan women first gained the right to vote in 1919, one year earlier than their American sisters. The first school for girls was opened in 1920, and by 1970, the Afghan government had raised the legal marrying age, abolished polygamy, and introduced mandatory educational requirements for girls. Things were better for a time.

But as with many worthy fights, progress wasn’t linear. The rights of Afghan women were largely stripped away by the mujahideen following their victory against the Soviets in the late 1980s; many of those rights were reinstated following international intervention in the country in 2001 and the two decades that followed.

Yet the Taliban takeover in 2021 ushered in a new era of such gender-based discrimination and violence as to make Gilead seem like the ultimate kingdom of equality. Currently, women are banned from activities including:

Attending higher education;

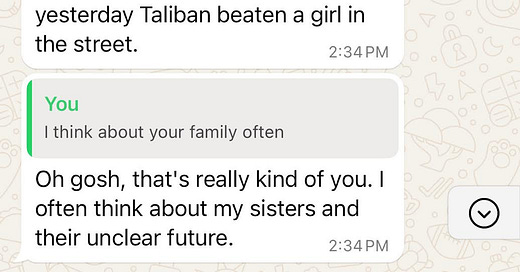

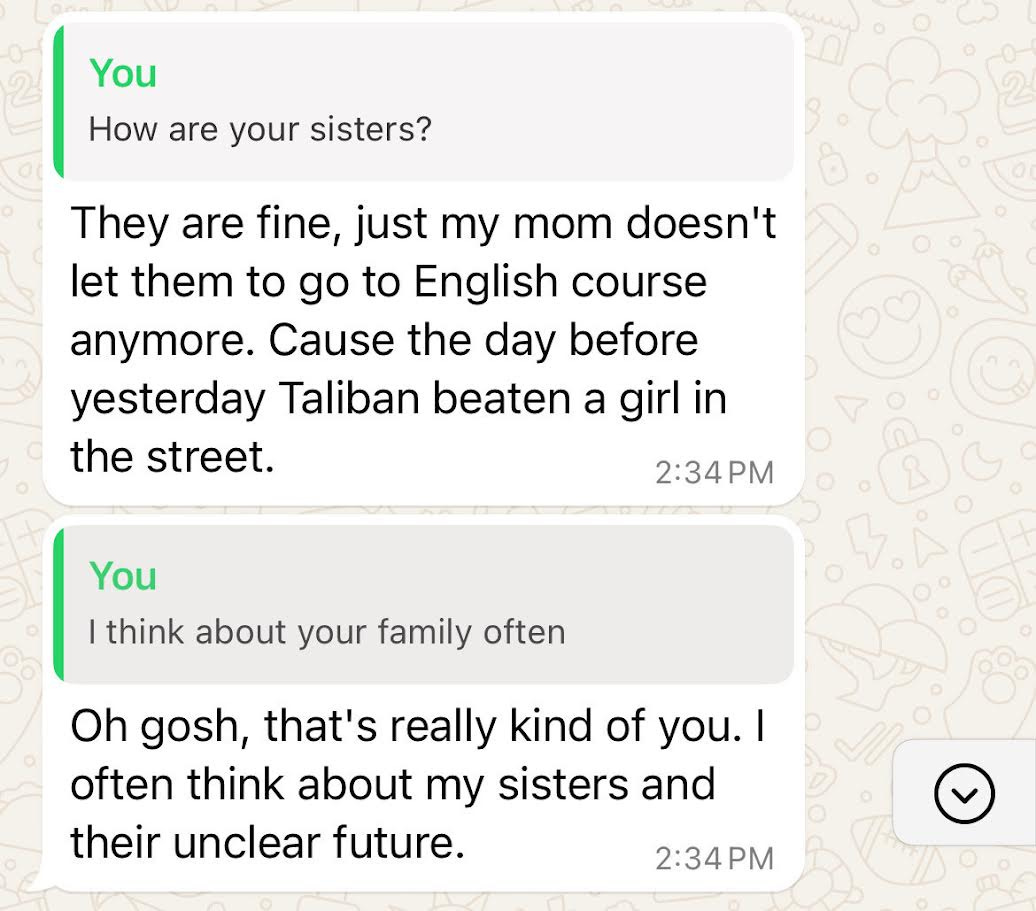

Attending public education beyond grade 6 (and lower in some provinces);

Attending non-segregated classes;

Obtaining transcripts or certificates for completed higher education programs;

Appearing in TV shows and movies;

Appearing on news channels without face coverings;

Working in nearly any capacity, including for international NGOs;

Traveling long distances without a mahram (a person with whom marriage is prohibited due to their close blood relationship, breastfeeding, or marriage) and a “legitimate reason;”

Entering a health center or cemetery without a mahram;

Traveling on public transportation without a mahram;

Obtaining a driver’s license;

Attending parks, gyms, or beauty salons; and

Participating in sports.

The codified penalties for any of the above include the severance of limbs, public floggings, public executions, and any other version of punishment the Taliban deems appropriate. Of course, there are non-legalized penalties, as well. Notably, activists have “carefully documented what amounts to an undeniable systemic pattern of sexual assault in Taliban-run prisons and detention centers.” Given the stigma of sexual violence in Afghanistan, these attacks are akin to a death sentence:

it [has been] speculated that some . . . women had been murdered by their families in “honor killings,” because they were sexually assaulted while detained. I n other cases, the evidence suggests they were killed by the Taliban who detained them. Women who resisted rape were also killed. Others commit suicide.

There can truly be no healing from such attacks.

Yet the monsters are hungry for more. In a recent series of “vice and virtue laws,” the Taliban have prohibited women from showing their faces in public, speaking in public (or in a manner that can be heard from outside their own homes), and looking directly at men to whom they aren’t related. It’s a grotesque assault on women’s mere existence; as Sahar Fetrat concludes, “Reducing their voices and bodies to things and sources of sin is an egregious act of sexualizing and objectifying women. These laws attack women’s personhood and autonomy, contributing to their further erasure from society.”

So where do we go from here? First, let’s stop publicly wagging a finger at the Talibs while entertaining them behind closed doors. We are the oxygen to the Taliban’s flame, fueling the fire as it reduces women’s rights to mere ashes. As per Shukria Barakzai, Afghanistan’s former ambassador to Norway, “‘It is concerning that international organisations, particularly the United Nations and the European Union, instead of standing against these inhumane practices, are trying to normalise relations with the Taliban. They are . . . disregarding the fact that the Taliban are committing widespread human rights violations’.”

What’s more, several mechanisms exist by which accountability could be meted if we desire to do so. (This article by Heather Barr covers these options far better than I ever could.) Take the International Criminal Court (ICC) as an example. In October 2022, prosecutors were authorized to resume their investigation into grave crimes committed in Afghanistan, and yet no formal judicial action has been taken since that time. In contrast, prosecutors formally requested arrest warrants in May 2024 for perpetrators on both sides of the current Israel/Palestine conflict, suggesting that justice can be swift(er) upon the instruction of the Court.

As for the United Nations, the Human Rights Council is currently in session until October 2024. Barr recommends that the Council establish a formal mechanism by which to collect and preserve evidence related to the Taliban’s crimes; renew the mandate of the special rapporteur while increasing their resources; and encourage member states to evaluate the pathways by which relief can be provided to victims. I stand by all these recommendations.

Of course, there’s a larger question looming here: how to penalize gender apartheid when it’s not formally a crime. (If you’re a legal hack like me, this is a great scholarly article discussing the legal mechanisms for criminalizing gender apartheid, including in Afghanistan.)

This is where it gets tricky. “International law” generally refers to those principles and norms that are so broadly accepted by the international community as to function as formal law in governing relations between states. However, it is left to international bodies such as the ICC and the International Court of Justice (ICJ) to not only define and codify these laws, but also to enforce them. Gender apartheid is not currently recognized as a crime under international law (although the argument can be made that it might qualify as a crime against humanity under several definitions of such), meaning that international judicial bodies lack a formal mechanism by which to penalize the act. Yet “[i]ncalculable numbers have been killed, with many more denied dignity, freedom and equality in their daily lives. It is truly shameful that the world has failed both to recognize systematic oppression and domination based on gender as a crime under international law and failed to respond appropriately to its gravity.”

And there’s a much more direct way to support the women of Afghanistan: going directly to the source. The Afghan female protesters are a genuine force to be reckoned with, relentless in their pursuit of equal rights. (In light of the Taliban’s recent restrictions on women’s voices, many have begun posting videos of themselves singing.) But the consequences of their defiance are severe, ranging from public beatings to indefinite detention. Standing by their side are several Afghan- and female-led organizations which offer critical support to the protesters in their greatest hours of need, many of which would benefit greatly from financial or other support.

In this respect, I cannot more highly recommend Task Force Nyx, a women-led non-profit whose bonds with the female protesters truly can’t be broken. Co-founders Laura and Sara lead with empathy and grace, and somehow contemplate all the tiny ways in which these women need support–including by arranging for escorts to greet the protesters upon their release from detention, often with flowers or letters of support in tow.

The hard truth is that the girl from the beginning of this column is real. She exists in this world, but she will not survive without our help. Because the Taliban has an army, and so must she.

There is also a relentless assault ongoing in this country. Women are dying now because of the Republican assault on healthcare for women, the latest is the Louisiana ban on a medication needed to prevent severe loss of blood during miscarriage by classifying it as a controlled dangerous substance. This reclassification of a safe and effective medication recommended by the World Health Organization is insane and is a measure of the insanity planned for women under a Republican administration. We have met the enemy and he/she is us.

There's really only one thing women are good for in Afghanistan under the Taliban: bearing children. How I wish sometimes that every woman of childbearing age in Afghanistan would lose the ability to procreate until this evil regime annihilates itself.